- Fintech Brainfood

- Posts

- 🧠 Everyone wants to be a bank

🧠 Everyone wants to be a bank

Plus; JP Morgan explores letting clients trade crypto, while also freezing the accounts of Blindpay and Kontigo

Welcome to Fintech Brainfood, the weekly deep dive into Fintech news, events, and analysis. You can subscribe by hitting the button below, and you can get in touch by hitting reply to the email (or subscribing then replying)

Weekly Rant 📣

Everyone wants to be a bank.

More companies have applied for OCC banking charters in the past 6 months than I can remember. The temptation is to view this as a pro-business giveaway or opening the floodgates (cue the Oprah meme).

I have a different take: this is Fintech's coming-of-age moment.

Post-SVB and Synapse, it’s clear that an enforcement-only approach has not worked. Fintech institutions will now be subject to the highest levels of oversight and safeguarding, and that’s a very good thing. But with great charter, comes great responsibility (sorry to butcher the reference there Stan, RIP).

The market is shifting in two directions:

Own the Rails: Companies like Mercury moving from "Rent-a-Charter" (BaaS) to direct ownership. Better unit economics, less third-party risk (SVB/Synapse).

Go Horizontal: Brex and Navan building "Brex-as-a-Service" and "bring your own card" platforms for banks and large enterprises.

So I wanted to walk through who's getting a charter, what benefits they hope to reap, and how it will change the competitive dynamic between banks and non-banks.

Getting a charter became unreasonably hard

The SVB collapse left a vacuum. The BaaS meltdown (Synapse) left a scar. The answer to both is the same: Get your own license. The problem was that door was closed until recently.

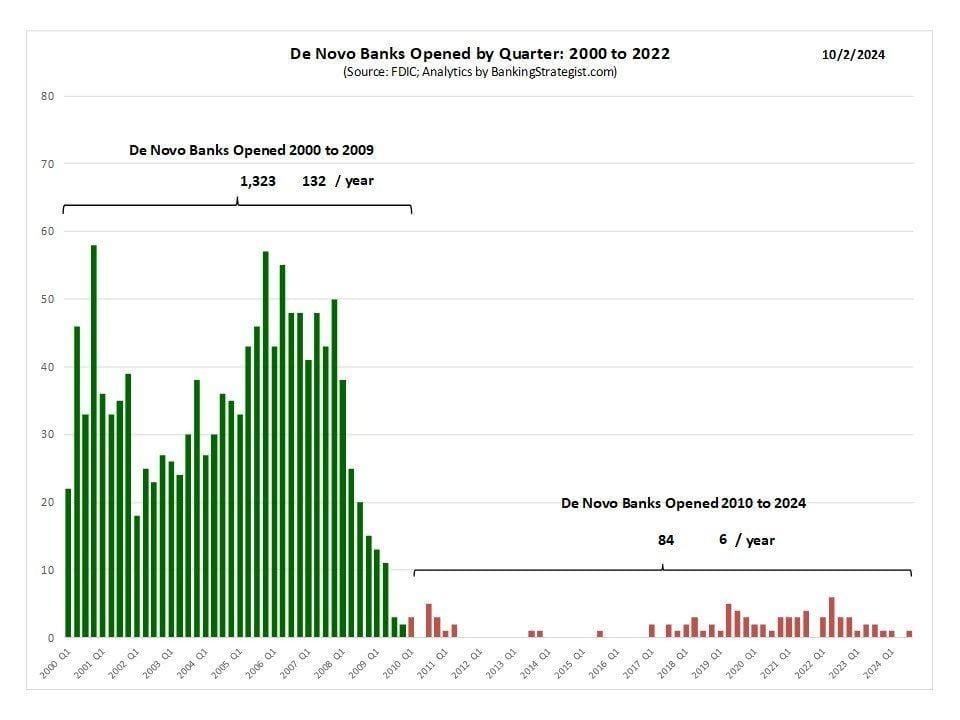

Since the global financial crisis, new bank formation dropped from a rate of 1,000/year to 6/year.

That’s one heck of a chart

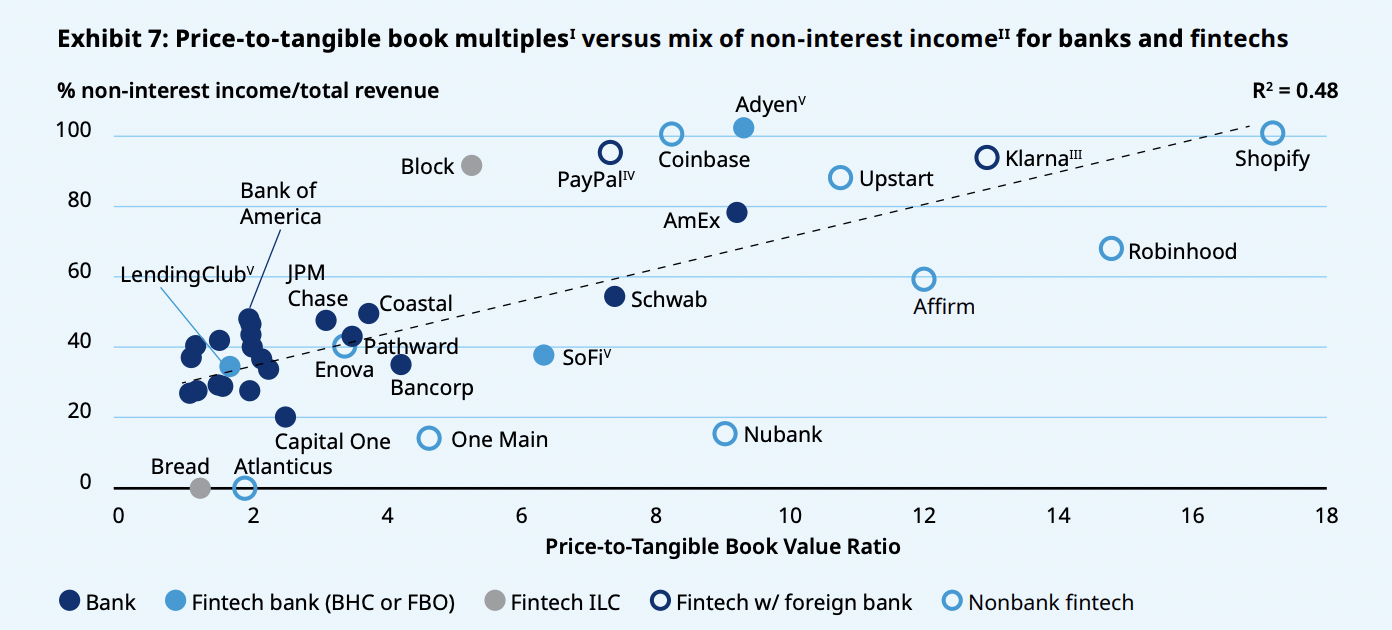

Historically, the valuation math for non-banks to become a bank didn't make sense. If you're a venture-backed tech company, you want a high revenue multiple. Banks didn't command high multiples. So companies went to lengths to prove they're not actually lenders or banks.

Fintech companies worked hard to be seen as anything but a bank

Cue the Neo dodging bullets meme

Banks and lenders are low-growth and low multiples. Their primary revenue source is Net Interest Margin (NIM)—the difference between what they pay out (on deposits) and what they take in (on loans). Under ZIRP, this margin gets brutally squeezed. Banks are capital-intensive: they must hold significant reserves and are heavily regulated. They are valued on metrics like Price-to-Book ratio, tied to physical assets. Reliable, but boring. That was the explicit goal of post-financial-crisis regulation.

Technology and payments companies are asset-light and high-growth. A payments company collects fees on transactions—revenue that scales with every user and isn't directly tied to interest rates. Successful software companies experience network effects. Critically, their costs don't scale as fast as their revenue (high operating leverage). Investors value these companies on high revenue multiples, betting on explosive future growth. Risky, but exciting.

This valuation gap created an incentive to avoid the label "bank" and strive for the "tech/payments" designation. Examples of this jujitsu:

Square/Block: Offers "Cash App Borrow" (functions as a short-term loan), but emphasizes its role as a payments facilitator. Its valuation is driven by Cash App and Seller ecosystems, not its lending book.

Earned Wage Access (EWA): Companies like DailyPay offer access to wages before payday. They structure this as a technology service fee rather than interest, arguing they are not lenders.

Buy Now, Pay Later: Firms like Affirm or Klarna market their services as a "budgeting tool" rather than a loan product, aiming for e-commerce multiples.

Regulatory jujitsu suited an era when interest rates were low, and the regulatory barrier was impossibly high.

Both facts have now changed.

The regulatory green light

Unlike the UK, Brazil, or the Netherlands, the US never had a post-financial-crisis effort to create a path for new, innovative banks. So while Revolut, Adyen, and Nubank got banking licences in their home markets, that wave never hit the US.

That's changing.

In addition to a more accommodating policy, the administration has been more directive. (Per Oliver Wyman and QED):

"This administration has funneled policy decisions on bank regulation through Treasury and has been willing to direct agencies in a manner previously unseen. This centralization may drive a consistently favorable posture toward fintech charters across prudential regulators."

But don't mistake this for a zero-sum game. While Fintechs get a seat at the table, Banks are getting a bonfire of red tape: a watered-down Basel III, the delay and reset of open banking mandates, and a defanged CFPB.

It's also a mistake to view this as a return to the chaotic, 'move fast and break things' era of 2021. It's the opposite.

The 'Sponsor Bank' model was built on a dangerous arbitrage: massive, complex Fintechs hiding behind the balance sheets of tiny, state-chartered community banks that often lacked the resources to police them. By granting direct charters, regulators are closing that loophole. They are effectively telling Fintechs: 'Come out from behind the curtain.' Direct supervision by the OCC or the Fed trades the opacity of the partner model for the transparency of federal oversight.

The three paths to becoming a bank

To understand what's happening, we need to examine the specific motivations of companies applying. Just as Revolut, Adyen, and Nubank are three very different European companies with different business models, so too are Erebor, Stripe, and Circle in the US.

Each path reflects a different bet on what matters most: owning the balance sheet, accessing the rails, or optimizing unit economics.

Charter Type | FDIC-Insured Full Charter | National Trust Bank | MALP (Georgia Charter) |

|---|---|---|---|

Who's applying? | Nubank, Erebor, Mercury | Circle, Ripple, Paxos, Bitgo, Bridge | Stripe, Checkout |

What is it? | The "Full Stack." Accept retail deposits, issue loans, access Fed Discount Window. FDIC insurance + heavy capital requirements. | The "Custodian." Federal charter to hold assets and settle payments. Federal preemption, but no lending, no FDIC insurance. | "Network Node." State license to join Visa/MC directly as a principal member. No deposits, no lending. |

Their goal? | Vertical Integration. Eliminate partner bank reliance, serve industries others shun (crypto/defense). Capture full NIM. | Settlement. Access FedNow/Fedwire directly to make stablecoins redeemable at low risk and lower operating costs. | Unit Economics. Cut out the sponsor bank "tax" on every card swipe. Margin expansion. |

If you are lending, the difference to your unit economics is meaningful:

If you’re lending then the cost of capital is the cost of your inventory.

Why a charter is worth the pain

Anything worth having requires work.

The rationale boils down to three things: control, economics, and legitimacy.

Control. In the partner model, every UI change or T&C update sits in a compliance queue for weeks. Partner banks decide if they're willing to take the risk of your business model—some blanket ban industries like crypto or defense. A charter lets you define your own "Risk Box" (Erebor's entire thesis: underwriting hard-tech founders legacy banks won't touch). It lets Mercury launch novel credit products without waiting six months for a partner bank's lawyers to understand the term sheet.

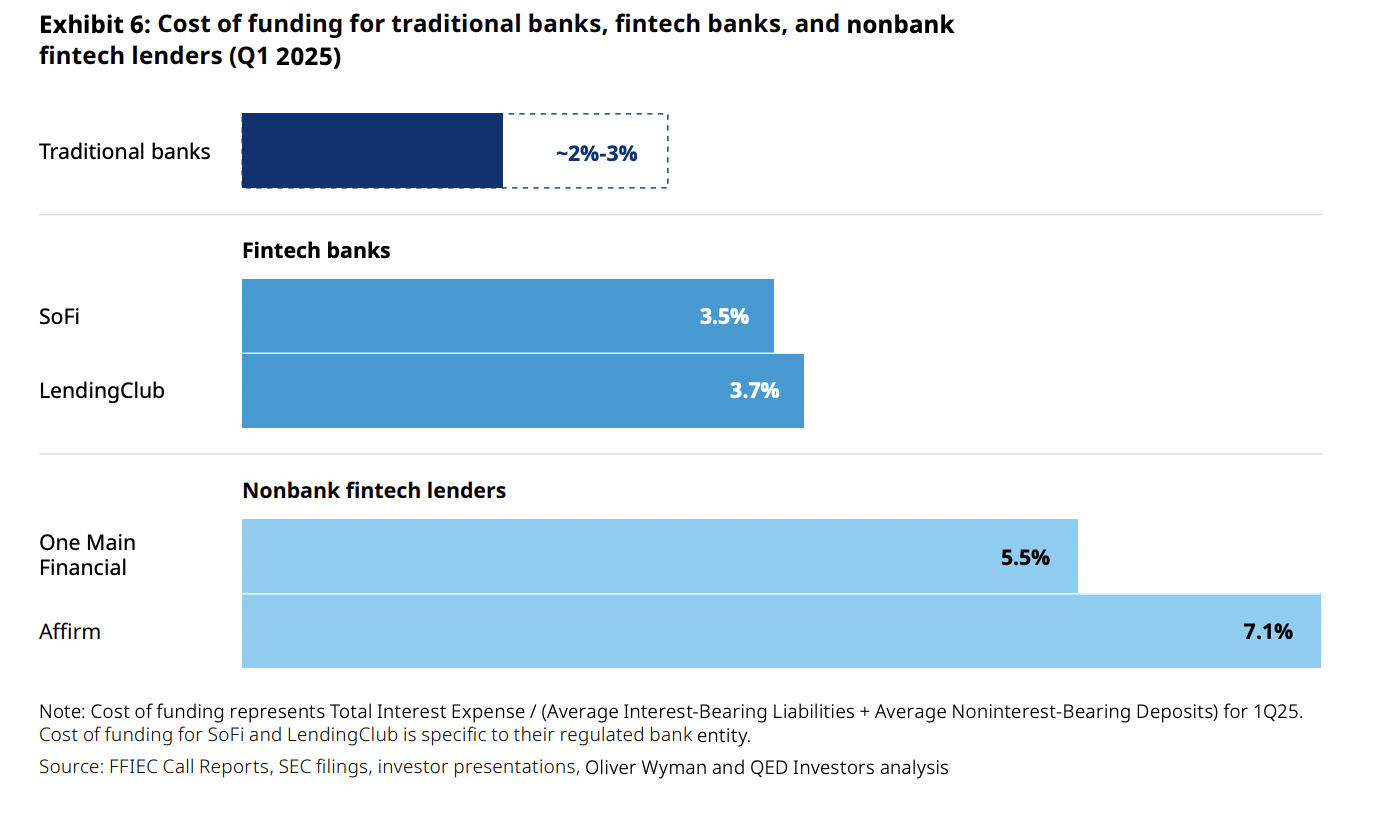

Economics. Relying on a sponsor bank means sharing the economics and inheriting their tech debt. A charter grants principal membership with Visa/Mastercard or access to the Fed. Stripe isn't doing this for prestige; it's doing it to avoid the sponsor bank tax on every swipe. The cost of funding chart above tells the story: traditional banks pay 2-3%, nonbank lenders pay 5.5-7.1%. That delta is the prize.

Legitimacy. The partner model forces you to play telephone. You talk to the bank, which talks to the examiner. Nuance is lost, and the default answer is "No." Paxos proved that negotiating directly with federal supervisors builds the trust required to get "first-of-kind" products approved. Some larger partner banks mandate onboarding steps (wet signatures, specific FICO cut-offs) that kill conversion. With a charter, you decide what constitutes "safe."

The idea that bank valuations must suck has also changed.

Look at Klarna, Nubank and Adyen:

Not all charters are valued equally

Nubank is an outlier among outliers. The vast majority of its revenue is from lending operations. It’s a giant purple, glowing exception to the rule that makes you wonder how long it will be before we have other public, chartered banks that lend, proving that growth is the most important factor in multiple, not the business model.

There's a gap in the market for growth-focused, tech-first banks.

The secret door: Fed payment accounts

Behind secret door number four is a path that doesn't get enough attention: the Fed's "skinny payment account." It proposes a world where an institution can access the Fed's payment rails (FedNow, Fedwire) without the requirement to lend or the safety net of the Discount Window.

Why is this the Holy Grail?

It solves the 'Run' Risk: If an institution holds 100% of customer funds in a master account at the Fed, there is no risk of insolvency. A "Narrow Bank" in the purest sense.

It's the Stablecoin endgame: For issuers like Circle and Paxos, it means much better unit economics, redeeming stablecoins at par to the dollar without worrying about commercial bank risk (SVB redux).

It legitimizes a new business model: The Payment Utility. A company that looks like a bank, settles like a bank, but takes zero credit risk.

If you're not a lender (like Mercury is becoming), not fighting "debanking" (like Erebor), and not trying to get better card economics (like Stripe), then a payment account plus National Trust Charter could be the perfect combination.

A CTO whose payments company has access to other global central bank RTGS systems told me:

"When we got direct RTGS access, our per-unit cost of payments dropped by 10x."

With that level of economic benefit, you'd wonder why everyone isn't becoming a bank.

Who's not getting charters?

You shouldn't like things just because people tell you you're supposed to.

There is another way. Not all Fintech companies have to become banks. Just ask Navan, Brex, and Ramp.

Their thesis is that banking is a commodity "utility" (like electricity), and the real enterprise value lies in the Operating System that sits on top of it. They don't want to hold the money; they want to direct it, help it flow, maybe help money do yoga occasionally. (You know, to avoid the Mindflyer or Vecna’s arm).

Why they are opting out:

Speed: You cannot build "Self-Driving Money" if you have to ask a federal regulator for permission to update your code.

Focus: They believe the problem isn't "moving money" (banks do that fine); the problem is "wasting money," lack of enterprise adaptability, and travel that sucks.

The players

Ramp is growing so fast, why bother with the distraction? Ramp is one of the fastest-growing companies in any category, including AI. Getting a charter and dealing directly with regulators could slow that down. They are happy to let a partner bank hold the deposits while they build the automation layer that controls the purse strings.

Brex (The "Enterprise OS"): Remember, Brex did apply for a charter in 2021—and then withdrew it. That was a strategic pivot. They realized they didn't want to be a "Bank for Startups"; they wanted to be the "Dashboard for the Global CFO." They are now building "Brex-as-a-Service" (powering cards for Navan).

Navan (The "App Layer"): They are the furthest up the stack. By partnering with Brex for payments, they prove you don't need a license to monetize money movement. They are betting that the user interface (Travel & Expense) is the only moat that matters.

While Ramp competes directly with Amex's travel cards business, Brex and Navan are partnering directly with banks as software platforms. That is a monumental shift and would be a narrative violation just 4 years ago.

The real danger: becoming Foxconn

The market is splitting into two distinct species:

The Financial Institutions (Mercury, Erebor, Stripe): They are vertically integrating to lower costs and own the rails. They will win on Net Interest Margin and Reliability.

The Software Wrappers (Ramp, Navan): They are staying asset-light to move fast. They will win on User Experience and Workflow Automation.

The Danger for Banks: The "Software Wrappers" are effectively treating banks like dumb pipes. If Ramp controls the dashboard where the CFO makes decisions, the underlying bank becomes invisible (and easily swappable). Banks are risking becoming the "Foxconn" to Ramp's "Apple"—essential, capital-intensive, and low-margin, while the software layer captures all the value.

There's still room for specialists (like sponsor banks who support Brex and Ramp).

There's still plenty of room for the mega banks who have deep pockets and giant enterprise customers.

But there's no room for small and mid-sized banks caught on their heels, trying to figure out what to do. There's no room for banks that aren't either tech-first or partnering with companies that are.

And most of all?

There's no room for complacency.

Fintech's adolescence was about avoiding the "bank" label.

Its adulthood is about earning it.

The companies that understand the difference will define the next decade.

ST.

4 Fintech Companies 💸

1. Beycome - The AI-assisted home buying journey

Beycome charges sellers a flat fee to list their home, close, and aims to save sellers on average $13,185 in fees while improving the overall experience for both buyers and sellers. For a flat $399, they’ll take 25 HDR pictures, list with NMLS, and make a virtual tour YouTube video.

🧠This feels like the upstart challenger to OpenDoor. They’re going deep into title, insurance, appraisal and even drone tours. That entire journey of stuff an agent just does and then makes high fees for. It makes sense, and maybe there’s room for someone other than OpenDoor to do it. Not sure I see the “AI” in all of that though.

2. Givefront - Spend management for nonprofits

Givefront helps nonprofits issue spend cards, track receipts ,and manage spend against pre-set budgets. Importantly, it can help ensure every transaction follows IRS 990 grant restrictions and donor policies with built in blocks and restrictions. The budget tracking is built around grants and shows the “spenddown” against those.

🧠The compliance of being a nonprofit is non-trivial. The center of gravity is the grant and the donation tracking instead of revenue. When you realize that, and the compliance that follows it, expense management tools for most companies don’t fit. This is the kind of scaled-niche that should do well if they can hit that vein of distribution. Where do nonprofits hang out? (rhetorical)

3. Speed Wallet - A stablecoin wallet

Speed wallet lets users instantly send USDT or Bitcoin, swap between those assets and instantly buy from stores (like Amazon or Starbucks) from within the app. They have 1.2m users and are based in the UAE.

🧠Tether is becoming the default international, consumer version of the dollar. There are probably 1000s of these mid-sized wallet apps that buy/sell/hold/send and its always with Tether. Despite many misgivings about its transparency reports, it has wild product market fit and isn’t going anywhere any time soon.

4. Transparency Analytics - Credit ratings for private credit.

Transparency Analytics will review a company’s financials within hours and share a credit assessment with the lender that has full transparency on how the decision was reached. Lenders can upload documents, model scenarios, and produce methodology reports for enterprises who value that transparency and compliance.

🧠 Private credit is booming, so it makes sense that the tools to support it would too. What’s different about TA to the traditional ratings firms (Fitch, Moody’s etc), is as the name suggests, giving the full breakdown of how they got to the decision. Which helps the lender make their decision faster too.

Things to know 👀

The information reported that the account freezes were linked to business activity in high-risk regions, including Venezuela, and to gaps in customer identity checks. From Tradeweb: “JPMorgan acted after seeing rising disputed transactions and chargebacks tied to these accounts. The bank said the decision was based on risk controls, not opposition to stablecoins themselves.”

To understand this, there are a few things we need to unpack:

🧠 There are three players here. Checkbook, JP Morgan, and the start-ups themselves.

JPM banks Checkbook.

Checkbook "banks" Kontigo.

Kontigo banks the End User.

When the End User commits fraud, the loss travels up the chain. If Kontigo can't cover it, Checkbook pays. If Checkbook can't cover it, JPM pays. If JPM spots a sanctions violation. It nukes the whole thing.

🧠 A high volume of chargebacks can lead to a program manager (e.g., Checkbook) incurring penalties and ultimately being removed from a card network. So you’d expect the PSP (if they were the program manager) to exit a subprogram (such as Kontigo) if it were a risk.

🧠 The CEO of Kontigo points out that Checkbook was however not its on-ramp or cards partner. The CEO says Checkbook provided virtual accounts. My bet is this is confusing ACH returns as “chargebacks.” Or it could be that, while the “self-custodial” account funds the card, the card itself is still custodial and may be causing disputes and chargebacks.

🧠 A common fraud pattern:

Bad Actor links a stolen/fake US bank account to Kontigo (via Plaid or micro-deposits).

Bad Actor "pushes" money to their Kontigo Virtual Account via ACH.

Kontigo credits the ledger instantly (or T+1).

Bad Actor swaps to USDC and withdraws to a self-custodial wallet (irreversible).

The US Bank sends an ACH Return (Insufficient Funds or Unauthorized) 2–3 days later.

Checkbook (and JPM) are left holding the negative balance.

(FWIW, Sardine* is a specialist at catching this exact pattern)

High ACH return rates (unauthorized returns > 0.5%) are a "kill switch" metric for banks.

🧠 Self-custodial cards are low-friction, easy to open, and ideal for this kind of fraud. It’s entirely possible that Checkbook (as a virtual card provider) saw this and had a fiduciary obligation to stop it. It’s also entirely possible that the CEO is right, and this was simple de-risking, leaving a start-up out in the cold.

🧠 For a bank like JPM, Venezuela is radioactive. It’s entirely possible JP Morgan’s AML system saw transactions to Venezuela, a sanctioned country, and issued a block. As a bank, it’s better to be safe than sorry (see the history of multi-billion dollar fines for sanctions violations). If Kontigo is marketing specifically to Venezuelans (which they appear to do), JPM might view the entire program as a sanctions evasion vehicle.

🧠 The Kontingo CEO argues that Checkbook repeatedly assured Kontingo they could offer global accounts “including Venezuelan migrants, as long as they passed the KYC/KYB process.” Reports suggest Kontigo’s US Terms of Service prohibited Venezuelan users, but their marketing (and reality) targeted them. There’s a disconnect here.

🧠 My read? A lot is getting lost in translation between bank speak, reporters and founders who (rightly) view the banking system as antiquated, but also, don’t understand why some of its rules exist and what they could do to mitigate them.

I haven’t spoken to anyone; all I’ve done is read the reporting and counterclaims.

The same bank whose CEO called Bitcoin a "hyped-up fraud" and "pet rock." The same Jamie Dimon who said, "If I were the government, I'd close it down." Now appears to be building a trading desk.

What changed?

🧠 Regulatory green light. The OCC 2025 is systematically removing barriers through more than six interpretive letters; banks can now custody crypto, hold tokens for gas fees, and act as intermediaries in trades. Crypto is now officially "standard banking activity."

🧠 Client demand. Most importantly for JPM, an increasing number of JPMorgan's institutional clients already trade crypto. They just use Coinbase Prime, not JPMorgan. Every hedge fund asking for access is a relationship they could monetize better.

🧠 Competitive reality. Goldman has a crypto derivatives desk. Standard Chartered is trading spot. Bank of America just enabled 15,000 advisors to recommend crypto. PNC launched direct Bitcoin trading last week. The question is who captures the institutional flow. Banks? Coinbase?

🧠 Dimon's evolution tells you everything about the crypto Overton window. At a time when market prices are falling, institutional adoption is accelerating.

Good Reads 📚

This piece posits that the successor to the petrodollar is the GPUdollar, and the GPUdollar is a stablecoin. Why? Well the petrodollar started as an offshore dollar in the 1970s following the collapse of the Bretton Woods system. Stablecoins are now playing a similar role in the global south. GPU debt instruments are being priced in dollars:

At some point compute will be tokenised, as we already see with projects such as io.net, and that shift will need stablecoin rails. When market participants buy or sell compute, many of them will use stablecoins because these give cheap, programmable settlement for buyers and sellers across the world.

🧠 Compute is the new oil, and you can see this in the number of chips deals the USA is doing with the middle east.

Tweets of the week 🕊

That's all, folks. 👋

Remember, if you're enjoying this content, please do tell all your fintech friends to check it out and hit the subscribe button :)

Want more? I also run the Tokenized podcast and newsletter.

(1) All content and views expressed here are the authors' personal opinions and do not reflect the views of any of their employers or employees.

(2) All companies or assets mentioned by the author in which the author has a personal and/or financial interest are denoted with a *. None of the above constitutes investment advice, and you should seek independent advice before making any investment decisions.

(3) Any companies mentioned are top of mind and used for illustrative purposes only.

(4) A team of researchers has not rigorously fact-checked this. Please don't take it as gospel—strong opinions weakly held

(5) Citations may be missing, and I’ve done my best to cite, but I will always aim to update and correct the live version where possible. If I cited you and got the referencing wrong, please reach out